Test-driven development (TDD) can be a deceivingly complex topic to approach. While the underpinning notion of Developer Testing has been understood and accepted for decades, the practice of TDD itself has often been misunderstood or oversimplified to a level that leads to a failure in fully grasping the nuances of the approach and the benefits born out of the same.

This can be quite evident in gatherings of Software Engineers were quite often the majority will say they approve of TDD as an approach, however only a small minority will admit to actively using it in their day to day.

As is often the case, one of the core reasons behind whether a particular approach is adopted or not is Return-On-Investment (ROI). While the negatives of TDD seem clear to all and mainly revolve around cost, the oversimplification of the approach obfuscates the majority of the positives leading to a poor perceived ROI. In this article, we hope to expose the benefits of the approach whilst also highlighting that while there is a cost, it is not proportional to what one might expect based on experience gained in more traditional Software Development techniques.

The Common Misconception

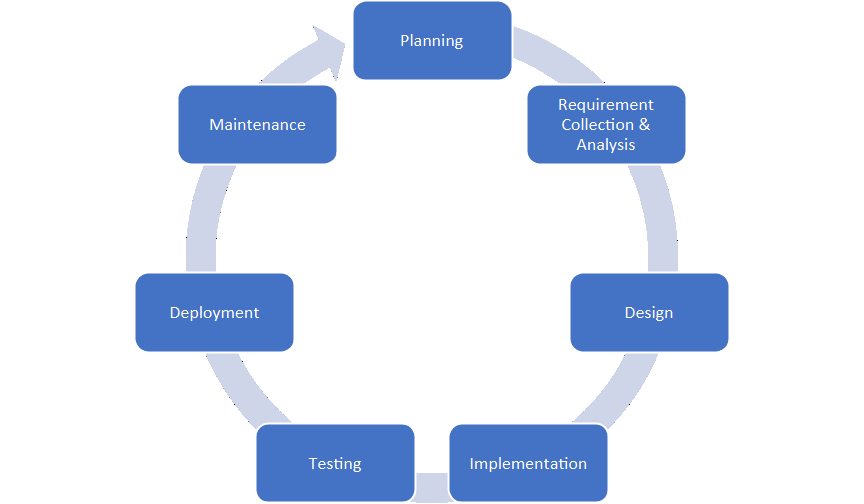

A common assumption is that TDD imparts little change to the traditional Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC). We are swapping around the order of the Implementation and Testing stages. This is a false assumption. In fact, the TDD approach imparts considerable change to what one would consider a traditional SDLC.

This common misconception is often what leads to lack of adoption. If all we are doing is writing our tests before our implementation, the negatives are obvious:

-

We are giving priority to the Test Suite over the actual implementation.

-

We are asking our developers to switch to a new SDLC, which at the very least will have a learning curve (a cost in terms of man-hours).

The only perceived benefit would be a better Test Suite. However, is having better tests so critical to us that it warrants the above risks? The answer to that is probably “no”.

Moreover, the above SDLC does not impart any insight into whether we are doing Developer Testing at all. The separate Implementation and Testing steps are usually understood to be handled by different individuals, if not departments. That was the common approach coming out of the 1970s, where the underpinning idea was that a Developer should not test his own code. Later evolutions of this flow dating from the early 1990s introduced the concept of Developer Testing as Unit Testing, an approach spearheaded by Kent Beck. Beck was one of the pioneers of Unit Testing, and later TDD, Agile Software Development and eventually Extreme Programming.

Nowadays most will agree that Developer Testing (especially in the form of Unit testing) is an intrinsic part of the Implementation phase. TDD further intertwines the processes of Design, Implementation and Testing much more closely together.

Test-First development (TFD)

Before we can discuss TDD, we need to start with its precursor, Test-First Development (TFD). Confusing the two is where the common misconception lies.

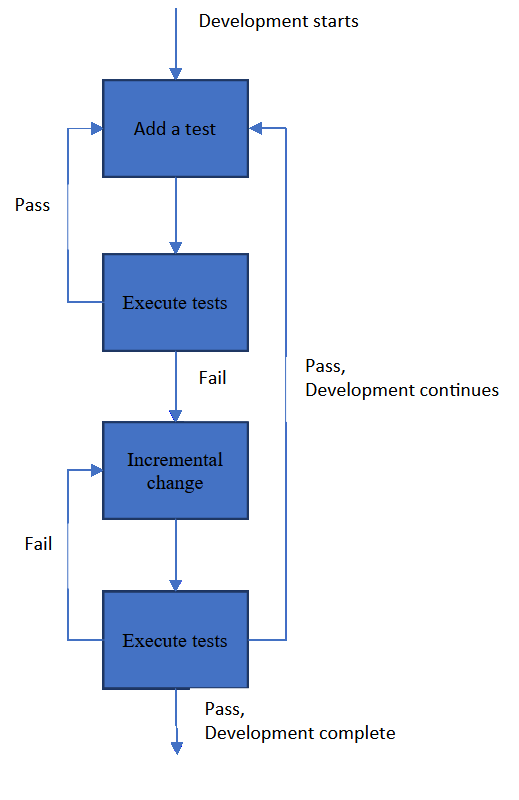

The above flow is what often comes to people’s minds when discussing TDD. You start with a test, and then you add the implementation. While this is not true TDD, TFD already introduces a number of benefits.

This deceptively simple change has deep repercussions. It shifts focus away from jumping straight into implementation and instead forces you to focus on defining the test case correctly.

Should the testing approach be bottom-up or top-down? Which requested feature does this test cover?

Moving on to the implementation that will make the test pass, the thought process behind the effort becomes completely different. We are entirely focused on one small, well-defined item of work, i.e. making our test pass. This simplifies and streamlines the process immeasurably. We have only a single problem to fix here.

Another core concept introduced here is that development should be carried out in terms of small, incremental changes. This has a deep impact on the agility of the development and the quality of the codebase. We are not only implementing the system by satisfying one test case at a time, but the implementation needs to be the most minimal possible implementation that will make the test pass. Thus we are effectively nullifying the risk of over-engineering the problem. We are delivering the simplest possible solution to this problem and nothing more. We are offering support for the requested feature, as requested, with no extra baggage tacked on.

A question that might arise here is, “won’t this process lead to a spaghetti system with no high level intelligent design behind it?” Well, here we are taking an evolutionary approach to design where we are hoping that by incrementally solving problems we eventually mature into a pattern that is well suited to solving said problem. Of course, this outcome is not guaranteed. If the system is sufficiently complex, the opposite will probably be true. Thus, we start shifting into a more mature model, i.e. TDD.

Test-DRIVEN development (TDD)

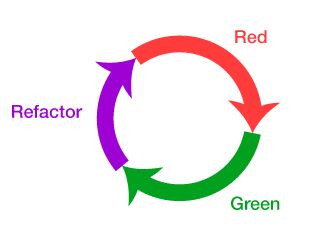

TDD builds on TFD by adding a refactoring stage to the process. Not only that, but refactoring is giving equal prominence as the other stages in the workflow, resulting in the well-known Red-Green-Refactor cycle.

Once again, the diagram does a good job of giving an easily digestible overview of the process. However, the beauty is in the details. Before delving into each individual stage, we must also discuss two high level approaches towards TDD, namely bottom-up and top-down TDD.

Bottom-Up TDD

The idea behind Bottom-Up TDD, also known as Inside-Out TDD, is to build functionality iteratively, focusing on one entity at a time, solidifying its behaviour, before moving on to other entities and other layers.

We start by writing Unit-level tests, proceeding with their implementation, and then moving on to writing higher-level tests that aggregate the functionalities of lower-level tests, create an implementation of said aggregate test, and so on and so forth. By building up, layer by layer, we will eventually get to a stage where the aggregate test is an acceptance level test; one that hopefully falls in line with requested functionality. This makes this a highly developer-centric approach mainly intended at making the developer’s life easier.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Focus is on one functional entity at a time | Delays integration stage |

| Functional entities are easy to identify | Amount of behaviour an entity needs to expose is unclear |

| High-level vision not required to start | High risk of entities not interacting correctly with each other thus requiring refactors |

| Helps parallelization | Business logic possibly spread across multiple entities making it unclear and difficult to test |

Top-Down TDD

Top-Down TDD, also known as Outside-In TDD or Acceptance-Test-Driven Development (ATDD), takes the reverse approach wherein we start building a system, iteratively adding more detail to the implementation and iteratively breaking it that down into smaller entities as refactoring opportunities become evident.

We start by writing an acceptance-level test, proceed with a minimal implementation. This also needs to be done incrementally. Thus, before any new entity or method can be created it needs to be preceded by a test at the appropriate level. We are hence iteratively refining the solution until it solves the problem that kicked off the whole exercise, that is, the acceptance-test.

This makes Top-Down TDD a more Business/Customer-centric approach. This approach is more challenging to get right as it relies heavily on good communication between the customer and the team. It also requires good citizenship from the developer as the next iterative step needs to be carefully considered. This process will speed-up in time but does have a learning curve. However, the benefits far outweigh any negatives. This approach results in the collaboration between customer and team taking centre stage, a system with very well defined behaviour, clearly defined flows, focus on integrating first, and a very predicable workflow and outcome.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Focus is on one user requested scenario at a time | Critical to get the Assertion-Test right thus requiring collaborative discussion between business/user/customer and team |

| Flow is easy to identify | Relies on Stubbing, Mocking and/or Test Doubles |

| Focus is on integration rather than implementation details | Slower start as flow is identified through multiple iterations |

| Amount of behaviour an entity needs to expose is clear | More limited parallelization opportunities until a skeleton system starts to emerge |

| User Requirements, System Design and Implementation details are all clearly reflected in the test suite | |

| Predictable |

The Red-Green-Refactor Life Cycle

Armed with the above-discussed high-level vision of how we can approach TDD, we are free to delve deeper into the three core stages of the Red-Green-Refactor flow.

Red

The Red-stage operates as outlined in TFD. We start by writing a single test, execute it (thus having it fail) and only then move to the implementation of that test. Writing the correct test is crucial here, as is agreeing on the layer of testing that we are trying to achieve. Will this be an acceptance level test or a unit level test? This choice is the chief delineation between bottom-up and top-down TDD.

Green

During the Green-stage we are tasked with creating an implementation to make the test defined in the Red stage pass. The implementation should be the most minimal implementation possible, making the test pass and nothing more. Run the test and watch it pass.

Creating the most minimal implementation possible is often the challenge here as a developer may be inclined, through force of habit, to embellish the implementation right off the bat. This is a mistake as assumptions will inevitably be taken and structure will be given to the code, but these will have been driven by the developer’s subjective opinion based on the current task and not on the requirements proposed by the tests. This will create technical baggage that over time will make refactoring more expensive and potentially skew the system based on refactoring cost.

The most minimal implementation to solve a problem can be so trivial that it can be easily missed in favour of a more complex solution, or the developer may feel that the incremental step forward is so minimal that it is not worthwhile. This behaviour is what one must learn to correct. We want the process to be iterative, and we want each step to be a small as possible. This is what will grant us agility.

Another key aspect is that the Red-stage, i.e. the tests, is what drives the Green-stage. There should be no implementation that is not driven by a very specific test. If we are following a bottom-up approach, this pretty much comes naturally. However, if we’re adopting a top-down approach, then we have to be a bit more conscious and make sure to create further tests as the implementation takes shape, thus moving from acceptance level tests to unit level tests.

Refactor

The Refactor-stage is the third pillar of TDD. Here the objective is to revisit and improve on the implementation. The implementation is optimized, code quality is improved and redundancy is eliminated.

Refactoring can have a negative connotation for many; being perceived as a pure cost, fixing something that was not done correctly the first time around. This perception originates in more traditional workflows where refactoring is primarily done only when necessary, typically when the amount of technical baggage reaches untenable levels, thus resulting in a lengthy, expensive, refactoring effort.

Here however, refactoring is an intrinsic part of the workflow and is performed iteratively. This dramatically reduces the cost of refactoring. The code is not being completely reworked. Instead, it is slowly evolving. Moreover, the code being refactored is by definition covered by a test; a test that has already passed in a previous iteration of the code. Thus refactoring can be done with confidence, resulting in further speedup. Moreover, this iterative approach to improvement of the codebase allows for emergent design which drastically reduces the risk of over engineering the problem.

It is of critical importance that behaviour should not change and no extra functionality should be added during the Refactor-stage. This allows refactoring to be done with extreme confidence and agility as the relevant code is by definition already covered by a test.

One might consider the global cost of refactoring to be still too large. However, consider the alternative; that is, dedicating time and effort up front to try to come up the final solution right off the bat. This has an obvious upfront cost. However, it also has an ongoing cost of ensuring the implementation does not drift from the original vision. In addition, this approach can easily fail. The original vision might have been incorrect to begin with, the original vision may have been correct but improperly communicated, or the team may have failed in upholding said vision. In all cases, we end up with lengthy, expensive, refactoring effort as previously discussed. Moreover, it gets in the way of providing value to the customer as early as possible.

Behaviour-DRIVEN development (BDD)

As previously discussed, TDD(or bottom-up TDD) is a Developer-centric approach aimed at producing a better code-base and a better test suite, whereas ATDD is more Customer-centric and aimed at producing a better solution overall. Behaviour-Driven Development may be thought-of as the next logical progression from ATDD. Dan North’s experiences with TDD and ATDD resulted in his proposing the BDD concept, whose idea and claim was to bring together the best aspects of TDD and ATDD whilst eliminating the pain points he identified in the two approaches. What he identified was that it was helpful to have descriptive test names and that testing behaviour was much more valuable than functional testing.

Dan North does a great job of succinctly describing BDD as “Using examples at multiple levels to create shared understanding and surface certainty to deliver software that matters”.

Some key points here:

-

What we really care about is the system’s behaviour

-

It is much more valuable to test behaviour than to test the specific functional implementation details

-

Use a common language/notation to develop a shared understanding of the expected and existing behaviour across domain experts, developers, testers, stakeholders, etc.

-

Surface Certainty is achieved since everyone can understand the behaviour of the system, what has already been implemented and what is being implemented and the system is guaranteed to satisfy the described behaviours

BDD puts the onus even more on the fruitful collaboration between customer and the team. It becomes even more critical to define the system’s behaviour correctly, thus resulting in the correct behavioural tests. A common pitfall here is to make assumptions about how the system will go about implementing a behaviour. This results in a test that is tainted with implementation detail, thus making it a functional test and not a true behavioural test. This is something we definitely do not want.

The value of a behavioural test is that it tests behaviour of the system and does not care about how it is achieved. This means that a behavioural test should not really change over time; not unless the behaviour itself needs to change as part of a feature request. This has a cost benefit over functional testing as such tests are often so tightly coupled with the implementation that a refactor of the code often involves a refactor of the test as well.

However, the larger benefit is the retention of Surface Certainty. In a functional test, a code refactor may also require a test refactor, inevitably resulting in loss of confidence. Should the test fail, we are not sure what the cause might be: the code, the test or both. Even if the test passes, we cannot be confident that the previous behaviour has been retained. All we know is that the test matches the implementation. This is of low value because ultimately what the customer cares about is the behaviour of the system. Thus, it is the behaviour of the system that we need to test and guarantee.

A BDD based approach should result in full test coverage where the behavioural tests fully describe the system’s behaviour to all parties using a common language. Contrast this with functional testing were even having full coverage gives no guarantees as to whether the system really satisfies the customer’s needs and the risk and cost of refactoring the test suite itself only increase with more coverage. Of course leveraging both by working top-down from behavioural tests to more functional tests will give the surface certainty benefits of behavioural testing plus the developer focused benefits of functional testing whilst also curbing the cost and risk of functional testing since they’re only used where appropriate.

In comparing directly TDD and BDD, the main changes are that:

-

The decision of what to test is simplified; we need to test behaviour

-

We leverage a common language which short-circuits another layer of communication and streamlines the effort; the user stories as defined by the stakeholders are the test cases

An ecosystem of frameworks and tools has emerged in order to allow for common language based collaboration across teams, as well as the integration and execution of such behaviour as tests by leveraging industry standard tooling. Examples of this include Cucumber, JBehave and Fitnesse to name a few.

Familiar Territory

If the above discussed workflows and paradigms ring familiar, it is because they are at the cornerstone of the agile philosophy.

As per the Agile Manifesto, we value:

-

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

-

Working software over comprehensive documentation

-

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

-

Responding to change over following a plan

In order to adhere to the Agile Philosophy as outlined in the manifesto, we do not really need to adopt a particular methodology or framework. However, adopting a well established, well documented and understood methodology with a track record of success does of course make things easier. It helps define a process and clear rules that if adhered to will help a team in achieving its agile goals. This is especially helpful when the team or company has little prior experience in agile. Examples of this include Scrum, Kanban and Extreme Programming.

In the same way that adopting a high-level methodology can help by giving more structure through a well-defined process, the same applies to picking an appropriate Software Development Process/Technique. While techniques such as TDD, ATDD and BDD could conceivably be applied to projects not following an agile methodology, the technique itself will inevitably push the team towards a process that exemplifies the values of the Agile Philosophy:

-

Bringing pain forward

-

Onus on collaboration between customer and team

-

Common language shared between customer and team leading to shared understanding

-

Imposes a lean, iterative process

-

Guarantee the delivery of software that not only works but works as defined

-

Avoid over-engineering through emergent design, thus achieving desired results via the most minimal solution possible

-

Surface Certainty allows for fast and confident code refactors

-

Tests have innate value VS creating tests simply to meet an arbitrary code coverage threshold

-

Tests are living documentation that fully describe the behaviour of the system

A Light in the Dark

Another key benefit to TDD and other similar techniques is in the area of study commonly referred to as Dark Code. Dark Code refers to systems or parts of systems that are unknown. Typically poorly documented, dependent on tribal knowledge within the team. As the knowledge is lost over time or through employee turnover, you are left with a system that nobody understands. Even worse, potentially there might be misinformation even at a customer level, with people disagreeing in regards to the system’s perceived behaviour. This no doubt will sound familiar to anyone responsible for what would be considered a Legacy System.

TDD, and even more so BDD, negate the risk of the above. As previously discussed, if correctly implemented, such techniques result in a test suite that fully describes the system’s behaviour. This is an incredibly powerful concept as it conveys a full picture of the system’s capabilities. Not only is there a well-defined set of behaviours that the system implements but there are no behaviours implemented that are not covered by a test. Apart from conveying the previously discussed Surface certainty, this would also allow for a complete rewrite of a system with extreme confidence. As long as the test suite passes successfully, the two systems are behaviourally equivalent.

This technique is in fact often used retroactively in order to facilitate moving away from an existing Legacy System. A set of behavioural or assertion level tests are created in an effort to represent the behaviour of the system. Once that is achieved, the system can be refactored or completely re-implemented with much greater confidence.

Conclusion

It is clear at this point that this topic is an extremely interesting, challenging and vast area of concern. Moreover, the adoption or lack thereof of such techniques is a crucial decision, effecting multiple layers of a company, which can have a large bearing on an effort’s chances of success.

We have also discussed how these techniques are deeply rooted in the Agile Software Development, having a shared history, having key players in common, and really being techniques proposed forward by said key players intended to facilitate the correct and successful adoption of their Agile Philosophies.

We have also discussed some (definitely not all) of the implicit and explicit benefits of working in this fashion. Again, this is a vast area of discussion and one can have multiple vast and highly important spin-off discussions rooted in this general topic.

Ultimately, it is my belief that if a team is working based on Agile Philosophies or based on a specific Agile Methodology, the discussed techniques are an invaluable tool. As previously discussed, they are not a requirement, and experienced teams/individuals will naturally tend to gravitate towards such techniques, possibly informally. In a wider context however, they are very powerful tools in ensuring that Agile Philosophies are upheld as well as help answering the daily questions and challenges that the team will face in attempting to uphold said philosophies.

In conclusion, we hope that this article has proven to be informative on the subject matter and will lead to a rekindling of the Test-Driven discussion. We really do feel it is worth another look.

An alternative version of this post was published on the phoenixNAP blog. You can find it here.

Nike ZoomX Invincible Run Flyknit 2 Review

Nike ZoomX Invincible Run Flyknit 2 Review